The noble North

Financial Times article March 2019

The house stood on a hillside above the inky-blue Atlantic, adrift in its own restless ocean of waving banana palms. The stone-and-whitewash hacienda had been here for more than three centuries, and the family of its owner more than five. The landscape’s ripe colours and fecund vegetation, and the softness of the air hereabouts, suggested somewhere in the Indian Ocean — Mauritius or Réunion, perhaps. But, no, I was in Spain.

I (and, I suspect, you) have never had much time for Tenerife. Until quite recently, I had tended to lump this Canary island in with the noisome costas of the Spanish peninsula: Tenerife, I believed, was Torremolinos for sun-starved Scandis craving a break from their long, dark Nordic winters.

What I know now is that there are two Tenerifes: south and north, well-trodden and much lesser- known. The southern part, sun-baked and arid, has the big scrappy resorts and sweeping dark- sand beaches that together account for roughly four-fifths of the island’s annual influx of 4.5m tourists.

The island’s north, however, is another dimension. The narrow coastal fringe running from the Teno mountains in the far west to the Anaga massif in the east rears up quickly into crags draped with sub-tropical greenery. Threaded along the coast road lie pretty, sleepy towns such as Garachico and La Orotava, with cobbled squares and colonial houses in volcanic stone. And dotted around the countryside are the haciendas where the old Tinerfeño families have their rural seats.

Families such as the del Hoyo-Solorzano, who arrived in 1494 as part of an invasion force that would defeat the indigenous Guanche tribes and claim Tenerife for Spain. But Alberto del Hoyo, current owner of Hacienda de las Cuatro Ventanas and the eighth generation of the family, is no tweedy aristocrat. On the day I meet him he cuts a dapper figure in a half-length coat fashionably worn with black patent-leather boots, his shaved head setting off lean, aquiline features.

Despite having left his island at 17 for university and work on the mainland, he was drawn back to Tenerife summer after summer as if by a powerful undertow. In 2011 he and his sister Ana inherited Cuatro Ventanas (“four windows”), the family estate on the coast near Los Realejos. Turning his back on his metropolitan life in Madrid, where he worked as a strategic consultant at advertising and marketing agency Ogilvy, del Hoyo moved back to oversee the transformation of the near-derelict hacienda into what, two years later, it eventually became: an upscale rural lodging whose six individual villas can either be rented separately or together (and with or without a full- time chef and chauffeur).

It was in 2018, however, that del Hoyo really got busy. Within the last 12 months he has acquired and restored two more historic north-coast haciendas (El Cardón and El Socorro), opening both to the public along the lines of Cuatro Ventanas. Late last year, he added three more properties to his portfolio — a grand aristocratic mansion, an architect-designed villa, and a townhouse — though these houses continue to belong to friends of his well-connected family, his role being that of a managing agent. The six properties are now marketed under del Hoyo’s newly created tourism brand, Be Tenerife, which also offers visitors a range of trips and experiences. Tenerife and “top- end” have rarely belonged in the same Google search — del Hoyo is changing all that.

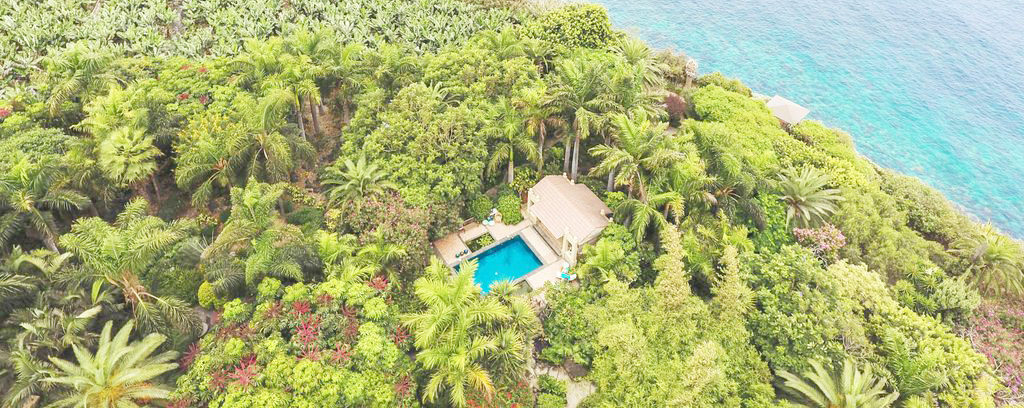

My villa at Cuatro Ventanas, part of which had once been the hacienda’s formal drawing room, had beamed ceilings of Canarian pitch-pine, chandeliers and heirloom furniture, gently sloping floors that creaked under the feet, and shuttered windows that could be flung open to bring the Yves Klein blue of the ocean into the room. Walking sticks stood in an old umbrella stand. Beyond the house was a pool with a view down the coast and an exuberant subtropical garden with garish flowers like jungle birds, all created and tended by del Hoyo’s mother Maribel.

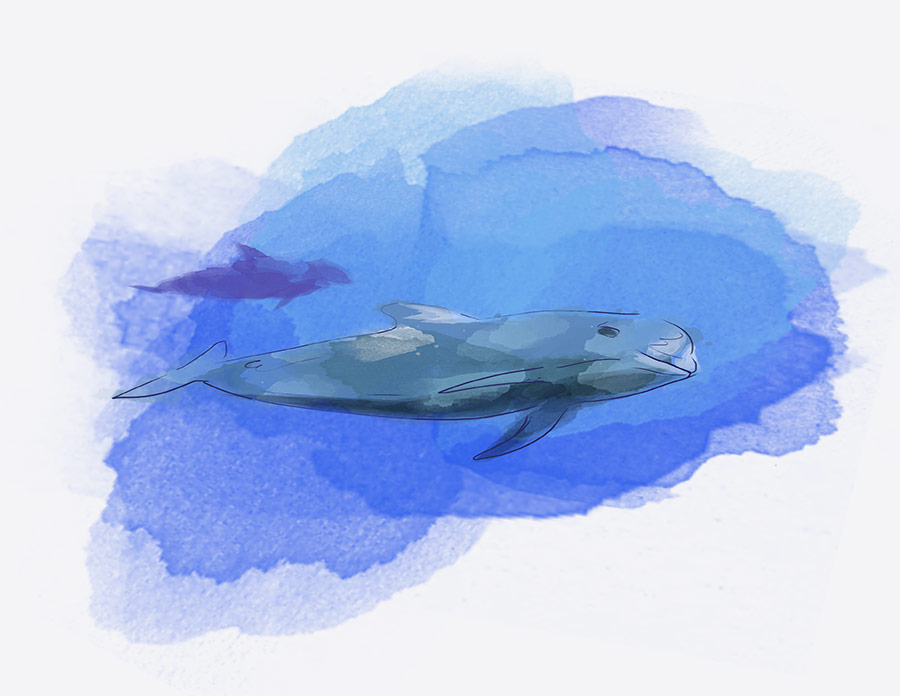

Picking his way among the jungle as he gave me a tour, del Hoyo confessed that he’d had no experience in hospitality before embarking on his project, but relied on an innate sense of what cultured and adventurous travellers would find appealing in his island. A crucial part of the remit was to show clients those aspects of Tenerife that you won’t find in the mainstream brochures. Which means adventures in local gastronomy, wine, art and history, hikes in the island’s wild upcountry, whale sightings from both above and below the water, and encounters with fascinating Tinerfeños who also happen to be del Hoyo’s friends.

Together we set out from Cuatro Ventanas for a spin around Be Tenerife’s other five properties, which are all located within a radius of 25km. Down a lane towards the sea through a forest of banana plants stood La Palapa, a sumptuous collection of three houses in a style combining elements of Africa, Bali and Provence. The houses were hidden away in a hectare of prodigiously fertile tropical gardens — the work of architect and landscaper, and La Palapa’s owner, Antonio del Real — which guests have entirely to themselves.

As a group, del Hoyo’s houses were notable for their diversity. At one end of the scale were the traditional haciendas done up in rustic-minimalist style (bare stone and polished concrete), like El Socorro — in a sensational setting above a beach where white waves break on black sand — and La Casa Blanca, a charming townhouse on the main square of Garachico.

At the other extreme, behind a grand gateway in the genteel town of La Orotava, lay the Suites de Franchy. This 19th-century mansion with the air of an English country house is owned by Mita Cologan, Marchioness of El Sauzal, who still lives in one wing of the sprawling property. Her son Conrado Brier took us through formal gardens into a succession of drawing rooms with marquetry floors and gold-framed mirrors, stopping to point out the family’s most precious relic: the original silk flag flown over the then newly conquered island of Fuerteventura in 1404. Alexander von Humboldt, the Prussian explorer and scientist, stayed in the house, said Brier, in order to examine the garden’s huge and ancient drago palm, which he memorably described as “the oldest being on Earth”.

The weekend spooled out into a series of wondrous landscapes, curious flavours and meetings with remarkable people. One day I headed west towards Buenavista, a snoozy country town with an out- on-a-limb feel where gentlemen in berets meditated on park benches and shop assistants smoked in the street in the morning sun. Another day, I turned north-east towards the mountains of Anaga, Tenerife’s most spectacular wilderness. Here, nature guide Nayra Sánchez led me on a hike through phantasmagorical forests of laurel which, said Sánchez, had existed here since before the Ice Age.

Before and after the walks and talks there were halts at some of the north’s most forward-thinking restaurants — such as Aristides in Garachico, where chef Omar Páez exemplifies the new interest in island products and fresh takes on Canarian classics such as salt-boiled potatoes with hot sauce and rabbit en salmorejo.

Over a fine lunch at Haydée in La Orotava, Augustin García of Tajinaste winery showed off his range of aromatic and mineral-rich wines made from old indigenous varieties such as Marmajuelo, Listán Negro and Baboso. Until recently, said García, you’d be more likely to find Rioja and Ribera than Tenerife on local wine lists, but a new crew of young oenologists had begun working with the island’s varied terroir to make startlingly original wines.

Pioneers such as García himself and Enrique Alfonso (whose vineyards, 1,450 metres up in the stark, cold highlands of Vilaflor, are some of the highest in Europe) had held a tasting for a prestigious group of 12 international Masters of Wine the day before my visit.

On a balmy evening that felt suddenly like summer, del Hoyo held a soirée at his house, a stunningly repurposed former fisherman’s shack on a remote headland jutting into the Atlantic. The gathering included two of the high-profile Tinerfeños that del Hoyo can call on to give added depth to his clients’ immersion in secret Tenerife: Rafael Rebolo, director of the Canarian Astrophysical Institute, and Francis Pérez, a photographer specialising in oceanography and wildlife — begetter of the heart-rending image of a turtle bundled up in plastic cord that won a World Press Photo award in 2017. Pérez told us of his up-close encounters with marine mammals in some of the planet’s remotest waters. Meanwhile the stars came out, the sea pounded away below the house, and the Tajinaste white flowed freely.

Postscript: at the airport next morning, del Hoyo handed me a package in brown paper tied with string. I unwrapped it at home to find a large photograph of an Ethiopian Suri warrior wielding a knife that shone brightly in the darkness: a beautiful, if unsettling image. Del Hoyo had been too modest to tell me about his double life as a photographer whose “Mystic Valley” series won him Discovery of the Year at the 2018 Neutral Density Awards. His Pics 4 Pills scheme donates profits from the sale of his work to fund medical aid efforts among tribal communities in the Omo Valley. The man, like his beloved island, was a fount of surprises.

Details: Paul Richardson was a guest of Be Tenerife. Villas for two at Las Cuatro Ventanas start at €130 per night; the main house at La Palapa sleeps four, from €325 per night; doubles at the Suites de Franchy cost from €175